The Northwest Center for Fluency Disorders has diverse areas of research interests. Overall, we strive to improve communicative skills and abilities of clients with fluency disorders, as well as searching for neural aspects relating to the dysfunction and improvement of fluency. Current areas of research include: 1) sender/receiver dynamics during communication, 2) active and passive means to efficiently inhibit stuttering, 3) forming collaborative care models with counseling professions to treat individuals who stutter, and 4) examining neural functioning aspects of people who stutter using high density EEG and neural networking modeling.

Sender / Receiver Dynamics

As we communicate, we do so not only through what we say, but how we say it and what we do when we say it. For example, we can understand emotion, attention, and intention by looking at someone’s eyes and facial expressions. Additionally, the sender can “read” what the receiver, or listener, conveys back to them through their eye gaze, posture shifting, and other nonverbal factors. If a person who stutters produces a block, their listener may look away or shift their posture. This may convey that the disfluent episode makes the listener uncomfortable and is something for the sender to be ashamed of or avoid doing.

By understanding these various aspects to communication using biophysiological measures (skin conductance, heart rate, and EMG activity), eye tracking and behavioral coding measures, clinicians and clients can be better trained and prepared to treat increased communication naturalness, regardless of dysfluency. For example, does the age-old technique of disclosing that you have a fluency disorder actually aid in communication? Or will maintaining eye contact as you are speaking improve the communication experience?

We currently have the following sender receiver dynamics studies that we are recruiting participants for:

Participants’ reactions to typical and atypical speech: Participants will complete self-reported empathy and state emotional questionnaires then will watch videos of speakers while their skin conductance, heart-rate and surface jaw EMG activity are recorded.

Participants watch videos while heart rate, skin conductance, and muscle activity of the jaw are monitored.

Gender differences in reactions to typical and atypical speech: Participants will complete self-reported empathy and state emotional questionnaires then will watch videos of speakers while their skin conductance, heart-rate and surface jaw EMG activity are recorded.

Active and Passive means to inhibit stuttering:

Overt stuttering; syllable repetitions, phoneme prolongations, and postural fixations, can be all but eliminated when people who stutter hear or watch someone else speaking. Additionally, by hearing and seeing one’s own speech while they speak, overt stuttering can be reduced by 60-80%. We think that this occurs because our brains change how they plan to produce speech or how they correct for feeling and hearing our speech. By discovering better ways to reduce stuttering, clients can speak fluently more efficiently, instead of having to use various combinations of unnatural sounding fluency enhancing techniques.

We currently have the following stuttering inhibition studies that we are recruiting participants for:

Stuttering inhibition using synchronous and dysynchronous audio, visual and audiovisual signals: Participants who stutter will read phrases of recited material under various conditions.

Here is a video explaining the McGurk Effect, which explores the relationship between what we see and hear when we perceive speech.

Stuttering inhibition throughout syllable position in sentences using pantomime and silent rehearsal strategies: Participants who stutter will read phrases presented on PowerPoint slides under various conditions.

Forming collaborative care models with counseling professions to treat individuals who stutter:

Harrison, J. C. (2009). The hawthorne effect and its relationship to chronic stuttering. Retrieved from http://www.pediastaff.com/resources-the-hawthorne-effect-and-its-relationship-to-chronic-stuttering–july-10-2009

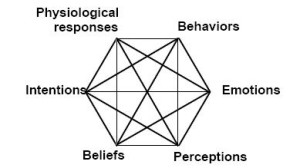

Fluency disorders encompass much more than just how we sound, it affects our emotions, socializing, and attitudes. Speech Pathologists are not adequately trained on treating emotional, social, attitudinal or bullying aspects relating to fluency disorders, but counselors are. Given how medical service delivery is moving to interprofessional service models, Speech Pathologists should adopt a similar approach. By treating emotional, social and attitudinal factors along with overt fluency, clients may achieve life long successes even if their level of fluency ebbs and flows. Fluency disorders encompass much more than just how we sound, it affects our emotions, socializing, and attitudes. Speech Pathologists are not adequately trained on treating emotional, social, attitudinal or bullying aspects relating to fluency disorders, but counselors are. Given how medical service delivery is moving to interprofessional service models, Speech Pathologists should adopt a similar approach. By treating emotional, social and attitudinal factors along with overt fluency, clients may achieve life long successes even if their level of fluency ebbs and flows.

Current studies are investigating the Speech-Language Pathologists and Counselor collaboration via questionnaires, however future studies will be focused on outcome measures from the two-week NWCFD intensive stuttering clinic to be held from Saturday July 26th through Saturday August 9th, 2014.

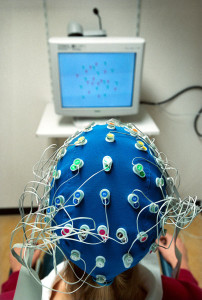

Examining neural functioning aspects of people who stutter using high density EEG and neural networking modeling:

It has been hypothesized that people who stutter exhibit neural differences in the planning of motor movements or the comparison of those planned movements to sensory feedback. We will use a 128-channel EGI EEG system to examine motor preparation aspects during stuttered and fluently controlled speech prior to and after attending the NWCFD intensive stuttering clinic. Additionally, we want to use these findings to support neural networking models to determine deficit areas in people who stutter. By understanding deficit processes involved with speech production and examining neural production variants when fluent speech is produced, we hope to better understand important factors to increasing fluency in people who stutter.

Current studies are using neural networking models of the Gradient Order of Directions Into Velocities of Articulators (GODIVA) and neural spike modeling with stuttered then fluency enhanced speech under the perception of second speech signals. Future studies will examine hypothesized neural relationships during altered states of speech production.